Pittsburgh isn’t fancy, but it is real. It’s a working town and money doesn’t come easy. I feel as much a part of this city as the cobblestone streets and the steel mills, people in this town expect an honest day’s work, and I’ve it (sic) to them for a long, long time.”

Willie Stargell 1

Pittsburgh has shed its working-class roots and is now a shining example of a post-industrial city. However, my love of baseball’s history makes it hard to separate today’s modern city from the hard-nosed players of the past, who made Pittsburgh into such a storied baseball town. These were the ones that lived up to the fan’s expectations for an “honest day’s work.” Guys like Honus Wagner, Bill Mazeroski, Roberto Clemente, Willie Stargell, and members of the city’s Negro League teams, certainly fit the bill.

The Wrong Pitch

“I don’t know what the pitch was. All I know is it was the wrong one.”

Ralph Terry 2

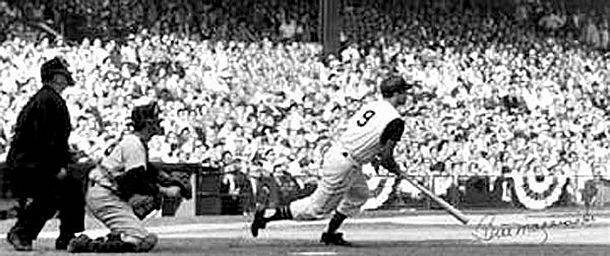

At 3:36 PM on October 13, 1960, William Stanley Mazeroski hit Ralph Terry’s 1 – 0 pitch over Forbes Field’s ivy topped, left field brick wall to make the Pittsburgh Pirates World Champions. His home run shocked the world and gave Pittsburgh a bright moment to always savor.

In 1960, Mazeroski was in the fifth year of his seventeen-year Hall of Fame career. Mazeroski played for what was essentially his hometown team. He was born in Wheeling, West Virginia, roughly sixty miles from Pittsburgh and raised in nearby Witch Hazel, Ohio. Bill lived with his parents and sister in a small one-room dwelling with no indoor plumbing or electricity. 3

Similar to Honus Wagner, the other iconic Pirate infielder, Mazeroski’s father was a coal miner of Eastern European descent. Mazeroski was of Polish descent, while Wagner’s parents were German immigrants. 4

The lifetime Pirate was elected to the Hall of Fame by the Veterans Committee based on his defensive prowess.5 He wasn’t flashy, was a mediocre hitter, but was a superior second baseman.

The Weird 1960 World Series

The mighty 1960 Yankees were the favorites to win the Series. After all, they had just won their eleventh American League pennant in fourteen years. 6

On the other hand, the public had few expectations for the Pirates. Their pennant was just their first in thirty-three years and only their fifth of the century. They were known as the “Battlin’ Bucs” since they had won 28 games after being tied or behind after the sixth inning.7 They were a fighting and scrappy bunch.

It was a weird and exciting Series.

When the Yankees won, they won big. In their three winning games, the scores were 16 – 3, 10 – 0, 12 – 0. Moreover, they outscored the Pirates 55 – 27 in the seven games. 8 Yet, for all their dominance, they couldn’t shake the Pirates. They left New York to play the final two games of the Series behind three games to two. The Yankees had to win game six to force the seventh game.

The final game was a seesaw affair. The Pirates fell behind in the early innings and were losing by three runs in the bottom of the eighth. Battling back as they were want to do, the scored five to go ahead, 9 – 7. Facing elimination, the Yankees tied the game in the top of the ninth.9

Mazeroski’s Home Run

Then, in the bottom of the ninth, Mazeroski’s leadoff home run ended the game. The upstart Pirates beat the powerful Yankees and were world champions. Pittsburgh has never forgotten the moment that Mazeroski’s ball flew over Forbes Field’s walls.

It was a towering fly ball that sailed over the ivy-covered, left field wall, 406 feet from home plate. As it did so, Yogi Berra, playing left field that day, turned and sadly ran towards the dugout. That piece of the wall is outside Pittsburgh’s PNC Park, behind a statue of Mazeroski celebrating his accomplishment as he rounds the bases. His cap is in his right hand with both of his arms triumphantly raised in the air.

Forbes Field’s Walls

What remains of the rest of Forbes Field’s walls are still standing where they always stood. However, the Joseph M. Katz Graduate School of Business and other parts of the University of Pittsburgh now occupy the area where the rest of Forbes Field stood.

On a sunny Saturday morning, I’m standing on the sidewalk in front of Forbes’ remaining walls. Trees have grown in what used to be the outfield. A granite sign announcing the school of business is between me, the trees, and the ivy topped walls.

I follow the line of red bricks inlaid in the sidewalk that outline where the rest of the outfield wall stood 10 as I walk over to nearby Pozvar Hall.

Forbes Field’s home plate is inside the building. “Near the spot where the likes of Honus Wagner, Roberto Clemente, Willie Mays, and Hank Aaron once batted, and where Babe Ruth launched the final three home runs of his career.”11 Superstitious students visit home plate before big exams, for good luck. Every October, fans gather to celebrate Mazeroski’s home run on the anniversary of the event.

Note that home plate is only “near” its original spot because the actual location is in the nearby women’s room.12 Thus are the vagaries of history

Columbus at Dawn

Earlier that morning, I left Columbus before the sun came up to make the three-hour drive to Pittsburgh. I left early so that I would have time to visit the Forbes Field location before attending that afternoon’s game between the Cubs and the Pirates at PNC Park. The teams were scheduled to play the following night’s game at the Little League World Series. Playing in the afternoon gave them time to make the short three-hour drive to Williamsport that evening.

My morning drive capped off a great week of baseball travel. On Wednesday, I drove to Cleveland to see the Indians play the Red Sox. The next day, I drove from Cleveland to Cincinnati to see the Reds play the Cardinals. Friday, I drove to the Louisville Slugger Museum and Factory and then back to Columbus. Saturday morning, I headed to Pittsburgh, pushing east into the morning sun as the dark sky turned to dawn. I drove over West Virginia’s hills, into Pennsylvania and finally through the Fort Pitt Tunnel under Mt. Washington.

On my approach to the tunnel, all I could see was the mountain towering in front of me. Then I was in the long, tile-lined tunnel with cars on either side. When I exited from the two-thirds of a mile expanse, Pittsburgh seemed to explode in front of me. It was possibly the most dramatic entrance to a city that I’ve seen. The drive from mountain to tunnel with nothing to see transformed into Pittsburgh everywhere. Pittsburgh’s skyline, bridges, and rivers were everywhere I looked.

Roberto Clemente

“Roberto Clemente’s greatness transcended the diamond. On it, he was electrifying with his penchant for bad-ball hitting, his strong throwing arm from right field, and the way he played with a reckless but controlled abandon. Off it, he was a role model to the people of his homeland and elsewhere. Helping others represented the way Clemente lived. It would also represent the way he died.”

Stew Thornley 13

Roberto Clemente Bridge

Downtown Pittsburgh is on a peninsula created by the confluence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio Rivers. Historic, Ft. Duquesne bordered by parkland is on the tip of the peninsula. My hotel was across the street from the fort and parks. I arrived early in the day and was not surprised that my room was not ready. So, I checked my luggage and made the short walk to PNC Park.

I walked the few blocks away from the Fort to the Roberto Clemente Bridge. The bridge is one of the “Three Sisters,” three nearly identical suspension bridges. The “Sisters” span the Allegheny River and connect Pittsburgh’s downtown to the city’s north side.

All three bridges are named for notable Pittsburgh residents. The “Ninth Street Bridge” was renamed for naturalist and Pittsburgh native, Rachel Carson, in 2006. The “Seventh Street Bridge” was named after Andy Warhol, another Pittsburgh native, in 2005. The “Sixth Street Bridge” was renamed after Clemente in 1998.

Interestingly, naming the bridge after Clemente was a compromise with the city. Despite public sentiment to name the new ballpark after the team’s greatest star, the Pirates sold the naming rights to PNC Corporation.14 Naming the adjacent bridge after Clemente gave the whole arrangement some balance.

The city closes the bridge to traffic on game days, which transforms it into a beautiful pedestrian crossway. Even though I’d been to a game at PNC park previously, I was excited to walk over the bridge for the first time.

“The Great One”

A riverboat passed under me as I walked over the Clemente Bridge. I could see fans gathering on the Riverwalk that runs behind the stadium. On the other side of the bridge stood the statue of Clemente, engraved with his nickname, “The Great One.”

As I approached the statue, I could not help that the day before I had held Clemente’s model bat that he, unfortunately, would never use. At the time, I was in the Louisville Slugger Bat Vault, holding the bat as a tour guide told the sad tale. Although the bat was ready for Roberto to examine in mid-December 1972, he never would. Only a few weeks later, he died in a plane crash on a rescue mission to earthquake-ravaged Nicaragua.

Clemente stood 5′ 11″ tall and weighed just 175 pounds but swung an unusually long, 36-ounce bat.15 He used the long bat to lash out at almost any ball that approached the plate. The ball skyrocketing to the far reaches of the park.

He played the outfield with a sense of reckless abandon and was one of the best defenders in history. Moreover, he had an unbelievably strong and accurate arm. His long, accurate throws from right field were awe-inspiring.

My favorite memory is how Clemente rolled his neck and stretched his back so that his chin almost touched his shoulder. The motion always reminded me of a proud thoroughbred that could run like the wind but was not entirely tamed.

Willie “Pops” Stargell

“INTIMIDATING PRESENCE BETWEEN THE LINES AND CHARISMATIC PATRIARCH IN CLUBHOUSE AND DUGOUT.”

Stargell Hall of Fame Plaque 16

Pittsburgh Post-Gazette

I walked from the Clemente statue down Federal Street past long lines of fans waiting for the gates to open. Many likely came early for today’s giveaway, a souvenir cardigan sweater. I didn’t understand the significance of the sweater giveaway until another fan explained that it was Mr. Rogers Day. Fred Rogers is another great American with near Pittsburgh roots, having been born in nearby Latrobe. The beige sweater zipped in front and had a little Pirates “P” over the left breast and was quite nice.

The statue of Willie “Pops” Stargell was just past the fans and gate.

“Pops”

“If he asked us to jump off the Fort Pitt Bridge, we would ask him what kind of dive he wanted. That’s how much respect we have for the man.”

– Al Oliver 17

If the Pirates had a “golden age,” it was the 1970s. Between 1969 and 1980, the Pirates dominated their division finishing first, six times, second, three times, and third, three times. Moreover, they won the World Series in 1971 and 1979. In the middle of it all, was the power-hitting Willie Stargell, the Pirates inspirational leader. Stargell became the de facto leader of the Pirates after Roberto Clemente died. Later in his career, he picked up the nickname, “Pops” which fit the persona of the aging, respected leader.

Stargell’s spotlight moment occurred when he led the Pirates to the 1979 World Series championship. The 38-year-old dominated the series as he led the Pirates back from a three games to one deficit. Over the seven games, he hit .400, with three home runs, and a World Series record 25 total bases. His majestic, sixth-inning home run in game seven, put the Pirates ahead to stay. 18

In his Hall of Fame career, Stargell finished in the top ten in MVP voting seven times. In 1979, he won the MVP award, was the World Series MVP, and Sports Illustrated’s Sportsman of the Year.

Occasionally, a player comes along who has impressive skills but also a real sense of pride in his craft. He also carries himself with a sense of dignity that other players respect and admire. It’s a small group: Jackie, Hank Aaron, and Stargell are vital members.

Into PNC Park

PNC Park is approachable and pedestrian in scale. Designed to fit within the existing city grid, it is also orientated to allow a great majority of spectators a spectacular view of the Clemente Bridge and the downtown skyline beyond. 19

I was having a good day in Pittsburgh. First, I visited Forbes Field. Then I walked over the Clemente Bridge and remembered two of baseball’s most respected players, Roberto Clemente and Willie Stargell. After some fish tacos and a couple of beers at “Steel Cactus,” I went inside the park. “Steel Cactus” is a Mexican place that is one of a series of PNC restaurants that are accessible to the outside pedestrian traffic.

As I walked to the team store to get my Pirates hat and then to my seat, I took in the gorgeous ballpark.

”The home of the Pirates is instantly recognizable as a ballpark, with architectural flourishes of Forbes Field lending a touch of nostalgia. The series of masonry archways extending along the entry level facade and decorative terra cotta tiled pilasters exude the charm of the club’s former home of 61 years.” 20

However, something was missing. When Mrs. Nomad and I first visited PNC Park a few years ago, we were more than impressed with Legacy Square. In 2006, the Pirates added the Legacy Square exhibits to honor Pittsburgh’s Negro League past via statues and interactive kiosks. What a fantastic way to celebrate the players and remember our unfortunate history.

Unfortunately, although I found the Square, the exhibits were gone. Instead, banners of popular Pirates and Negro League players were the only things I saw.

Sad End to Liberty Square

The Negro Leagues in Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh had a unique relationship with the Negro Leagues. Between 1927 and 1948 Negro League teams from Pittsburgh – the Homestead Grays and Pittsburgh Crawfords – dominated Negro League baseball. In that period, they won thirteen regional and five world championships. 21 They also fielded some of the greatest players of their era.

baseballhistorycomesalive.com

During the winter in 1937,22 Pittsburgh Courier sportswriter Chester Washington sent this telegram to Pittsburgh Pirates manager, Pie Trainer:

“KNOW YOUR CLUB NEEDS PLAYERS STOP – HAVE ANSWER TO YOUR PRAYERS RIGHT HERE IN PITTSBURGH STOP – JOSH GIBSON CATCHER FIRST BASE B. LEONARD AND RAY BROWN PITCHER OF HOMESTEAD GRAYS AND S. PAIGE PITCHER COOL PAPA BELL OF PITTSBURGH CRAWFORDS – ALL AVAILABLE AT REASONABLE FIGURES STOP WOULD MAKE PIRATES FORMIDABLE PENNANT CONTENDERS STOP – WHAT IS YOUR ATTITUDE? – STOP WIRE ANSWER”

Chester Washington – The Pittsburgh Courier 23

There was no response.

In 1937, the Pirates finished in third place with a record of 86 – 68.24 Even though they still won only 86 games in 1938, they finished in second place just two games behind the Cubs. 25 If the Pirates’ focus was solely on winning, wouldn’t adding some of the greatest players in history have improved their prospects?

brittanica.com

Of course, the Pirates weren’t alone in disregarding winning so that they could exclude black players from the Major Leagues.

Pittsburgh Pirates, Black Ballplayers Legacy

The Pirates were slow to integrate their team. They finally did so in 1954 when they added second baseman, Curt Roberts. They were the tenth team in baseball to integrate, and Roberts was the 42nd player of color in Major League Baseball. 26

Although they had a late start in integration, the Pirates “took the lead among MLB teams and unveiled the first all-black and Latino starting lineup in 1971.” 27

AP Photo/Gene J. Puskar

The Pirates also honored Pittsburgh’s Negro League past. In 1988, they commemorated the 40th anniversary of the Homestead Grays victory in the last Negro League World Series. The pregame ceremony honored living members of the Grays and the Pittsburgh Crawfords and a championship pennant raised atop Three Rivers Stadium. Possibly most importantly, Pirates team president, Carl Barger, “apologized for the role played by the Pirates and by Major League Baseball in perpetuating segregationist practices in baseball.” 28

”With this moment, the Pirates became de facto leaders in navigating the complex relationship between professional sport and race, and this comparatively small ceremony was, at the time, a truly groundbreaking moment for professional sport in America. Over the next two decades, the Pirates continued what they started by holding annual Negro leagues nights and installing permanent Grays and Crawfords championship banners at Three Rivers Stadium in 1993.”29

So, Where’s Legacy Square?

In 2006, the Pirates opened Legacy Square, an exhibit that celebrated Pittsburgh’s Negro League past. Central to the presentation was interactive kiosks and nine life-size, bronze statues of Pittsburgh’s greatest Negro League players, including five enshrined in Cooperstown. 30

At the opening ceremony, Pirates managing general partner Kevin McClatchy said:

“A lot of people probably don’t realize the incredible history we have here, Kids today probably don’t know about segregated players in different leagues, eating in different restaurants. … This will tell the story of the Negro Leagues. Because it is a huge part of our baseball history.” 31

Imagine my surprise when discovered that the statues were missing from Legacy Square. All I saw were a few banners of Pirates and Negro League players. Did I misremember?

Photo posted on post-gazette.com

No, I did not. When McClatchy sold the team in 2015, the new ownership led by Bob Nutting, decided to remove the statues. 34 All that remains are banners of Pirates and Negro League greats.

Fortunately, Sean Gibson, CEO of Pittsburgh’s Josh Gibson Foundation and Josh Gibson’s great-grandson, was able to gain control of the statues. He sold them at auction with the proceeds going to the Foundation.

All in all, it is a sad state of affairs.

Honus Wagner, Mazeroski and Home

A Girl Named Olivia

I had a great time at the game, and throughout, I talked to a young sixteen-year-old fan. I believe her name was Olivia. She’d driven in from Chicago with her father to see their favorite Cubs play. Hearing that she was a Cubs fan led to a conversation about my family’s recent first trip to Wrigley Field. We also talked about events in the game, how I kept score, and other things.

Be still my music-loving heart, but it turns out that Olivia is a musician who plays the violin. I asked who her favorite composers were, and she mentioned Brahms and Dvorak. Had she heard the Dvorak cello concerto (one of my favorites)? I asked. She hadn’t but did love the cello in general. I mentioned the second movement of Brahms’ Second Piano Concerto that has a wonderful cello part and she said she would listen to it.

Then we talked more about baseball and our conversation spread to the people in the row in front of us. They were also Cubs fans. I told them about my trip and how much I loved PNC Park.

When the game ended, I walked by Honus Wagner’s statue that is in front of the stadium. Wagner is the epitome of Pittsburgh’s working-class past.

Honus Wagner

Johannes Peter “Honus” Wagner, the son of German immigrants, was born in Chartiers (now Carnegie) Pennsylvania in 1874. His birthplace is roughly six miles from where his statue greets fans entering PNC Park. Wagner’s father was a coal miner for more than 20 years. None of his children wanted to work in the mines. Honus – then likely known as John – planned to become a barber, as one of his older brothers had. 35 Instead, Albert, another older brother, recommended that the team that he played for in Steubenville, Ohio, sign Honus. 36

Wagner was an “awkward-looking man…..oddly built – 5-feet-11, 200 pounds, with a barrel chest, massive shoulders, heavily muscled arms, huge hands, and incredibly bowed legs that deprived him of any grace and several inches of height.” 37 Yet he was an extraordinary ballplayer.

He was second to Babe Ruth in voting for inclusion in the initial Hall of Fame class. Other records include a league-record eight batting championships (tied with Tony Gwynn), seventh in career hits, third in triples, tenth in doubles and stolen bases. Remember, he retired 100 years ago!38 Most of all, he led the Pirates to four pennants and one World Championship.

His last public appearance was at the unveiling of the statue I admired. It first stood in Schenley Park outside Forbes Field, then at Three Rivers Stadium and finally at PNC Park. Wagner was too weak to get out of his car at the ceremony and just waved from the window. 39

Bill Mazeroski’s Statue

Before heading back to Clemente Bridge and my hotel, I walked up Mazeroski Way to pay homage to Mazeroski’s statue and the section of Forbes Field’s wall behind it. From there, I enjoyed the sunny day as I walked on the Riverwalk, towards the Clemente Bridge.

A few hundred feet in front of me, a couple of women asked a fan if they could have his “Mr. Rogers cardigan.” Unfortunately, he tried to sell it to them, and they declined the offer. I caught up to them and gave them mine. Better that they have it than me.

There was a massive crowd in my hotel’s lobby. Some of the people were attending a formal event in the ballroom. Others were football fans who were there to see the next day’s pre-season game between the Chiefs and Steelers. There were also three big busses outside. The rumor was that they were for the Cubs to drive up to Williamsport. Fans were gathered around them to see the players.

Williamsport was my next journey. I’d wanted to see the major league game at the Little League World Series since the televised event looks like such a lot of fun. However, the Little League restricts the game to the Little Leaguers and their families, which is how it should be. They play in a minor league stadium, which does not have the capacity to allow others to attend. Moreover, outsiders would destroy the event’s intimacy. Yet, I wish there was an exclusion for a certain Nomad.

On Sunday, I drove home and had a few days to relax, say hello to Mrs. Nomad and write about my travels. It had been a long but gratifying week. Possibly the best of my travels!

- Baseball Almanac – Willie Stargell Quotes

- Baseball Almanac – 1960 World Series – Game 7

- Bob Hurte, “Bill Mazeroski,” Society for American Baseball Research

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Baseball Almanac – New York Yankees Team History & Encyclopedia

- Bob Hurte, “Bill Mazeroski,” Society for American Baseball Research

- Sportslifer, “50 Years Ago Today, Bill Mazeroski Shocked The World” Bleacher Report, October 12, 2010

- Ibid.

- “PITT’S HISTORIC IMPACT – Baseball History Preserved at Pitt,” University of Pittsburgh Website

- Ibid.

- Roadtrippers.com – Old Forbes Field Home Plate

- Stew Thornley, “Roberto Clemente,” Society For American Baseball Research

- Wikipedia – Roberto Clemente Bridge

- John Altamura, “20 Biggest Bats in MLB History,” Bleacher Report, July 13, 2012

- National Baseball Hall of Fame – Willie Stargell

- Wikipedia – Willie Stargell

- Ibid.

- mlb.com – PNC Park Features

- mlb.com – PNC Park Features

- Wikipedia – List of Negro League Baseball Champions

- Ken Burns Baseball claims the date was the winter of 1938. See “Shadowball,” Chapter 18 “The Best”

- Paul Francis Sullivan, “The telegram to Pie Trainer and the lost Pirates pennant of 1938” The Hardball Times

- Baseball Reference – 1937 Pittsburgh Statistics

- Baseball Reference- 1938 NL Team Statistics

- Joe Posnanski, “The Integration Timeline,” July 11, 2015

- John Harris, “Is there no place in Pittsburgh League all-stars?” The Undefeated, November 1, 2016

- Josh Howard, “Disappointment in Pittsburgh: How the Pirates Ditched Pittsburgh’s Negro Leagues Past,” Sport in American History, October 12, 2015

- Ibid.

- Chick Finder, “Pirates put history on display,” Pittsburgh Post- Gazette, June 27, 2006

- Ibid.

- Josh Howard, “Disappointment in Pittsburgh: How the Pirates Ditched Pittsburgh’s Negro Leagues Past,” Sport in American History, October 12, 2015

- Josh Howard, “Disappointment in Pittsburgh: How the Pirates Ditched Pittsburgh’s Negro Leagues Past,” Sport in American History, October 12, 2015

- Ibid.

- “Honus Wagner, a Family History Researcher and Baseball,” Record Click – Professional Genealogists

- Jan Finkel, “Honus Wagner” Society for American Baseball Research

- Ibid.

- See Baseball Reference – Honus Wagner

- Jan Finkel, “Honus Wagner” Society for American Baseball Research