“Baseball is too much of a sport to be called a business and too much business to be called a sport.”

Philip Wrigley1

Bryce Harper is now happily ensconced in Philadelphia – Manny Machado and Nolan Arenado have signed big deals. In reaction, the Angels are considering a $350 million contract that will make Mike Trout an Angel for life.2 Pardon the pun.

Thus ends a contentious offseason where some players signed epic deals. However, I’m leaving on my spring training trip, and there are still critical free agents without a home. Moreover, some players are so disgruntled that they are discussing striking when the current Collective Bargaining Agreement (CBA) ends. I’m sure fans everywhere are wondering how millionaires could be so disgruntled.

So what gives?

I am a reasonably knowledgeable fan but have only a cursory understanding of the business issues at hand. So, I’ve decided to focus some of my attention and this summer’s blog posts on the current labor situation. In so doing, I hope to become better versed in the subject and so can you, if you want to.

To start, let me outline what I understand to be the issues that affect the current labor market situation. I’ll explore many of these in detail in later posts.

The Players Share of Baseball Revenues

Always remember that the players are the product. Fans don’t buy tickets to watch owners own or general managers manage. Fans want to see great players play. As such, the players should naturally expect to receive the lion’s share of MLB’s revenues.

These revenues continue to increase year over year. Total baseball related revenue in 2018 was a record $10.3 Billion. The sport has experienced dramatic revenue increases since 1992 when Bud Selig became commissioner. Revenue is up an inflation-adjusted 377%.3

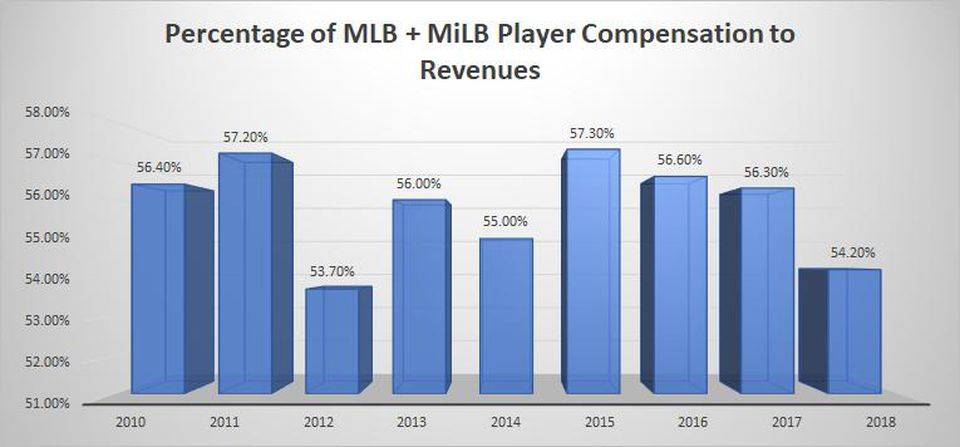

However, the players’ share of these record revenues has decreased from 57.3% in 2015 to 54.2% in 2018. This rate may have accelerated since signing the latest CBA before the start of the 2017 season.4

Why would payrolls decrease in a time of prosperity?

The disparity of Team Revenues

One argument is that some teams can pay higher salaries than others. Each team generates its income from ticket, concessions and merchandise sales. Significantly, each team receives different sums from their local TV and radio agreements. Thus, revenue per team is uneven, and only the higher earning teams can afford costly player salaries.

For example, in 2017, the top-earning team, the Yankees, generated $619 million in revenue. In contrast, the Athletics made the lowest revenue, $210 million. Median revenue was $281 million.5 Naturally, the A’s shouldn’t be expected to match the Yankees payroll.

The disparity is likely a factor, but only to a certain degree. If it was the only cause, then we would see a correlation between revenue and payroll. However, it’s hard to see this pattern. Note what happens when rank the teams by their 2018 opening day payrolls, leaving the 2017 revenue in the chart.6

While I expect some of these results, there is seemingly no correlation between revenue and payroll. As expected, the Red Sox earn a lot and pay a lot and the Athletics don’t. However, there are many teams that don’t spend what they could.

For instance, the Yankees earn the most but rank seventh in payroll, not first. Moreover, they don’t exceed the Red Sox by 50% as their revenue does. Also, their crosstown rival, the Mets rank seventh in revenue but twelfth in payroll. While the Braves and Phillies revenue only slightly lower than the Mets, both rank in the bottom third of the payroll list.

Payrolls and Investment Strategies

Apparently, the teams’ investment strategies and philosophies are also a factor. Discussing this issue is one of the reasons I will consider this issue over a series of posts. There is a difference of opinion as to how one builds a competitive team.

In my mind, part of the question relates to the expected return on investment (ROI) from each payroll decision. Moreover, why does one own a baseball team anyway? Is team ownership that lucrative? Could they make more money faster if they invested in another industry or the stock market? From a purely financial perspective, the owners should be generating an ROI at a higher rate than other possible investments. If not, they have other reasons to be involved. Maybe they enjoy the sport, the challenge, and the competition.

However, those in the front office are instrumental in these decisions and are trying to build a career. To do so, they likely need to prove that they can be both successful and profitable.

The great Connie Mack owned and managed the Philadelphia Athletics for about fifty years. In that time, he built many winning teams and then promptly sold his players to generate profits. An example of his philosophy was this famous comment:

“It is more profitable for me to have a team that is in contention for most of the season but finishes about fourth. A team like that will draw well enough during the first part of the season to show a profit for the year, and you don’t have to give the players raises when they don’t win.” [7]

Connie Mack7

I’ll discuss these motivational issues in a later post.

Noncompetitive Behavior

It follows that a good reason to consider management’s motivation is the wonderful phenomena of “noncompetitive behavior.”

There is a saying, “If you can’t win ninety games, you should lose ninety.”8 Teams don’t face penalties for losing too many games, and thus, there can be value in fielding an inferior team.

This “noncompetitive behavior” comes in at least two forms. The first is “tanking,” when an organization deliberately fields an inferior product to save money and garner higher draft choices. The second is when the organization “manipulates service time” to delay a player’s free agency. In so doing, they force the player to earn less than they should. I discuss this behavior in a subsequent section.

Each strategy is unethical. Anyone admitting to doing either would face a fine from the league or a grievance from the players union. However, organizations tend to use these tactics, and each can depress the players’ earning potential.

“Tanking”

In the case of “tanking,” the team takes the position that there is no reason to invest in a losing proposition. For one reason or another, the team is not good enough to vie for a championship. In these cases, MLB’s rules enable management to avoid signing higher priced players. Teams are also allowed to trade high priced veterans for prospects. In so doing, the team amasses a large number of good, young prospects that will drive future success. It also saves its funds so it can invest in the later years when the team is ready to compete.

But is the strategy always unreasonable and unethical? For example, the Astros are infamous for tanking after Jim Crane purchased the team in 20119 and hired GM Jeff Luhnow. However, the Astros already stunk. They finished the season before the purchase with 56 wins and 106 losses. At that point, why not build a successful franchise from the ground up so they could become a consistent winner? Would a group of older, higher price veterans have led them to the Promised Land? 10

In my mind, there are a series of different types of organizations. There is the premium group that invests wisely in both their farm system and major league club. Others follow the same path but don’t spend as wisely. Still more are unwilling to invest as they could. Then there are those that take a step back to rebuild. Finally, there are likely teams that unethically take a step really far back and “tank.”

I’ll delve into the subject in future posts. However, it’s clear that there are teams that underinvest possibly to the point of being non-competitive. The result is that players have fewer opportunities to sign high-value contracts.

Baseball has Become a Very Efficient Marketplace

Thus, some of the reduction in salaries is due to the organizations’ practices and philosophies. However, the players need to realize that they are negotiating in a very efficient marketplace. Moreover, they benefitted from an inefficient market for a very long time.

The Business Dictionary defines an “efficient market” as:

“A market where all pertinent information is available to all participants at the same time, and where prices respond immediately to available information. Stock markets are considered the best examples of efficient markets.”11

Business Dictionary

“Moneyball” describes how Billy Beane built an outstanding Oakland A’s team by taking advantage of an inefficient market. Beane and his staff used statistical methods to successfully value and select players in ways that other teams did not. The A’s derived better information and thus won many games with a payroll lower than the competition.

It follows that before the “Moneyball Era,” the players benefitted from this inefficient market. At that time, baseball management used the wrong metrics to value players. These metrics included a pitcher’s total wins and earned run average (ERA). Similarly, they evaluate position players using batting average runs batted in (RBI) and errors made in the field. The disappointing result was that weaker than expected players signed contracts for more than they could justify by their performance.

In contrast, although teams use different ways to value players, the resulting estimates are very consistent. The teams no longer overpay for players. The market is efficient and somewhat rational.

Manipulating Service Time Under the CBA

However, from the players’ perspective, the current collective bargaining agreement exacerbates the market’s effects.

The agreement requires players to be under team control for six years and thus can’t take advantage of free agency. However, the team can manipulate the players so-called “service time” to eke out an additional year of control.

An organization manipulates service time by assigning a player to the minor leagues at the start of their rookie season. When it promotes the player a few weeks later, his rookie season doesn’t qualify as service time. This behavior forces the player to play another season under team control.

It follows that younger players can offset service time issues if they get to the “bigs” early. If they are major leaguers when they are 19 or 20, they can be free agents at 26 or so. In so doing, they are much more appropriate for the long term deals that Harper, Arenado, and Machado signed.

However, some teams like to evaluate and draft college players. Additionally, some players want to go to college. These college graduates may need a year or so in the minor leagues. Thus, they may not get to the majors until they are 23 or so. Add six or seven years of service time, and they will not be free agents until they are 30. At that age, they may not be considered worthy of a long-term deal.

The Dilemma

As I will discuss in future posts, the current system is rife with problems and inequities. On the management side, some individuals want to be successful but are committed to investing wisely. On the players’ side, it’s difficult to maneuver to that big payday which is more than frustrating. Thus their total share of revenue is decreasing, and they are not happy.

Watch this space.

- http://www.wishafriend.com/quotes/qid/1353/

- https://sports.yahoo.com/report-angels-considered-offering-mike-155938907.html

- https://www.forbes.com/sites/maurybrown/2019/01/07/mlb-sees-record-revenues-of-10-3-billion-for-2018/#69b8e12e5bea

- Maury Brown, MLB Spent Less On Players Salaries Despite Record Revenues In 2018, Forbes Jan 11, 2018, https://www.forbes.com/sites/maurybrown/2019/01/11/economic-data-shows-mlb-spent-less-on-player-salaries-compared-to-revenues-in-2018/#3efcf88839d7. Includes Chart Below

- See Reddit “The percent of revenue each team spent on Opening Day player payroll” https://www.reddit.com/r/baseball/comments/a3e759/the_percent_of_revenue_each_team_spent_on_opening/

- https://www.reddit.com/r/baseball/comments/a3e759/the_percent_of_revenue_each_team_spent_on_opening/

- http://www.quoteland.com/author/Connie-Mack-Quotes/1902/

- Neyer, Rob. Power Ball. Harper. Kindle Edition

- Mike Ozanian, Houston Astros Sold For $610 Million” Forbes November 11, 2011, https://www.forbes.com/sites/mikeozanian/2011/11/18/houston-astros-sold-for-610-million/#740d5bc29cf6

- See “Astroball: The New Way to Win it All” by Ben Reiter. Crown Archetype for a complete account of how the Astros were rebuilt.

- http://www.businessdictionary.com/definition/efficient-market.html